How Long Can You Keep Used Cooking Oil

How clean cooking helps the climate

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

Wood-fired stoves have powered Nigerian cooking for time immemorial. But cleaner cooking could go a long way to saving lives, and carbon emissions, in Africa's most populous nation.

C

Catherine Chinenye's morning routine is one of early morning prayers and breakfast, before visiting her family's nearby cassava and yam farms in Umuekpe village, in south-east Nigeria. At the farms, she begins to tend the twisted tendrils of yam and blooming cassava stems.

From time to time, she adds bits of firewood to the heap in a corner of her farm. The firewood, she says, will serve for the sunset meal. Soon the fireplace will be lit, with a black pot resting on a hearth of three stones filled with smouldering charcoal and smoke.

Catherine shares this routine with 175 million Nigerians – more than the number of people living in the UK, France, Portugal and Belgium combined – who rely on wood, charcoal and other polluting varieties of biomass for fuel. Overall, nine in every 10 Nigerians lack access to clean cooking. On a global scale, the country comes only behind China and India in terms of the numbers of people living without access to clean cooking.

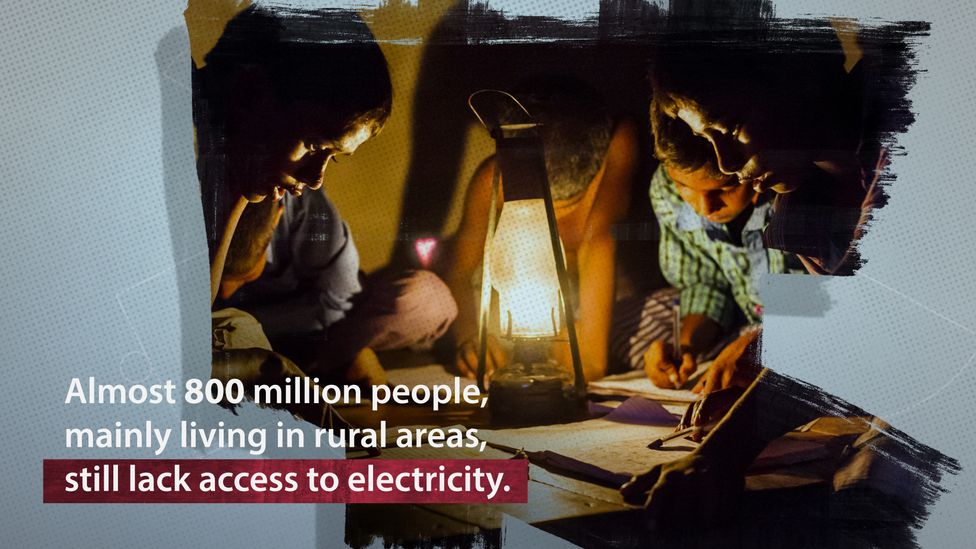

Around 10% of the world's population still does not have access to electricity (Source: World Bank, Credit: Adam Proctor/BBC)

Charcoal cooking is an age-long practise in rural communities in Nigeria, fed by the constant cutting of trees. In 2020, Nigeria lost 97,800 hectares (377 square miles) of natural forest, equivalent to 59.5 million tonnes of CO2 emissions.

The situation is also grim for health in the country. In 2016, more than 218,000 people died in Nigeria from household air pollution, including from inhaling smoke from open woodfires in the kitchen.

But more recently, the practice has also taken root in urban centres, says Adeola Ijeoma Eleri, chief scientific officer at the Energy Commission of Nigeria. She links this trend to a complex supply chain that starts with the "rampant and indiscriminate" cutting down of trees and the production of the charcoal in kilns close to cities.

Nigeria is a relatively small climate polluter on a global scale, due to its limited industrial activity. Despite having Africa's largest economy and its largest population, equivalent to 2.7% of the world total, it contributes 0.36% of global CO2 emissions. However, the country's CO2 emissions almost quadrupled between 1990 and 2019, from 28 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year to 92 million. Its emissions are expected to soar further with the ongoing population surge and economic growth.

This means Nigeria's path will be crucial in the drive towards global net-zero emissions in the next three decades – a goal the world needs to meet to limit global temperatures to 1.5C, according to the International Panel on Climate Change. At the UN's global climate talks in Glasgow, COP26, Nigeria made a pledge to reach net zero emissions by 2060. The country's leaders have also promised to cut emissions 20% by 2030 compared with business-as-usual levels, increasing to a 47% cut below business-as-usual by 2030, depending on whether the country receives international financial support.

The country's commitments on climate have earned it an "almost sufficient" score from analysts Climate Action Tracker (CAT), which notes that Nigeria faces one of the dilemmas of climate action. Despite its limited contribution to climate change in the past, it says, Nigeria will have to abstain from exploiting fossil fuel resources if the global 1.5C limit is to be kept.

But Nigeria will also have to look closely at its usage of charcoal and firewood, and find ways to cut it. Biofuels accounted for 86% of CO2 emissions from energy use in 2017 in the country.

It could exploit less polluting cooking sources such as electricity, gas, ethanol, solar and high performing biomass stoves. But a long-held cultural preference for charcoal and firewood, and high costs of alternative fuels could hamstring progress. Sharon Ikeazor, Nigeria's minister of state for environment, has said that 60% or more of all households in Nigeria will still be cooking with traditional biomass by 2030 if current policies continue.

Such new actions are clearly needed. But fixing the situation will come at a cost. With four in 10 Nigerians living below $2 (£1.5) a day, families often do not have the financial resources to pay for a clean stove and for the fuel or power to run it. Precious Ede, a professor of climatology at the Rivers State University in the Niger Delta region, says the income level of households in the country must be factored into any plan private investors and the government are bringing in to drive the net-zero target.

Some international actors are taking frontline roles. The Clean Cooking Alliance, a non-profit operating with the support of the United Nations Foundation to promote clean cooking technologies in low- and middle-income countries, is one of them. The alliance has initiated a series of programmes to improve access to clean energy in Nigeria, including research, funding for small- to medium-scale clean cooking businesses and behaviour change campaigns. It's no easy hack, and the clean cooking industry has not yet achieved the scale required to make significant impacts, according to the Clean Cooking Alliance.

On the global scale, progress is clearer. The share of the global population with access to clean cooking fuels and technologies grew from 47% in 2000 to 59% in 2016. Investment in the sector has increased as well, reaching $70m (£50m) in 2019, up from $43m (£30m) in 2018.

Traditional, polluting forms of biomass like charcoal and wood come with a health risk (Source: World Bank, Credit: Adam Proctor/BBC)

Increasing access to clean cooking is also a gender issue, says Ikeazor. Women, more than men, are likely to suffer significantly from the adverse effect of using polluting charcoal and firewood due to social-cultural practices that primarily restrict them to roles in the kitchen, especially in Africa. So focusing on a women-centred approach to clean energy solutions can both accelerate access and save lives.

This means ensuring that the solutions being rolled out actually work for the women using them. In one project last year, a group of non-profit organisations distributed clean cooking solutions to women in 50 households in Mararaba-Burum village in the federal capital Abuja. As well as supporting these women, the project aimed to collect data on how effective different stoves were at reducing air pollution inside their homes. It tested five types of clean stoves, all based on either liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), fuel-efficient biomass or ethanol, by attaching wireless sensors onto the cookstoves to track how long and how often women cook. The data, downloaded via mobile devices or tablets, was used to quantify emissions reductions as well as get data on how cookstoves were actually being used.

It found that the more efficient biomass stoves were used the most. The liquid fuel stoves showed the lowest use over the long term, due to the expense of buying LPG and difficulty in sourcing ethanol in the region. However, households said they would be more willing to take out a loan to buy an LPG stove than a biomass one.

Encouraging such a switch from biomass to LPG could reduce cooking's CO2 emissions in Nigeria substantially. But in the longer run, an overreliance on fossil fuels – including LPG – brings its own problems.

How to give clean electricity to 800 million people

Those who favour limiting investment in natural gas have raised concerns about the negative climate impacts, and the inherent health and climate trade-offs of using LPG for cooking. The Clean Cooking Alliance says it understands this and is prioritising further research on the impacts of LPG.

Perrine Toledano, head of mining and energy at the Columbia Centre on Sustainable Investment in New York, says there are better long-term opportunities for a developing country like Nigeria to solve its energy crisis with renewables such as solar than with natural gas. She says the country should not fall prey to locking huge investments in gas infrastructures that are now "less cost-effective than investment in renewables".

But there is another big concern about the use of LPG: its rising cost. The cost of 12kg of LPG spiked by 50% from 4,515 Nigerian Naira ($11/£8) in September 2020 to 6,165 Nigerian Naira ($16/£12) in September 2021, the National Bureau of Statistics says. In a report Eleri published this year on the growing clean cooking market, she recommended that the government bring in policies to keep the price low.

But since she published the report in May, the price of LPG has continued to increase, largely due to the reintroduction of tax on LPG importation. She is now concerned that if the price surge is allowed to continue, people who had recently started using LPG may go back to firewood and charcoal.

"Without a stable price regime, then all our efforts in pushing for a transition in the cooking energy sector will be in vain," she says. "The current cost of LPG is already a deterrent to households interested in making a switch. The most concerning part is some households that have made the switch are reverting to fuelwood and charcoal."

The rising cost is partly a reflection of the rising cost of natural gas in the international market.

With the concern around natural gas's environmental impact, electric cooking is another way to clean up cooking. But in Nigeria, and many other developing countries, electrification is not always simple.

Nigeria has made significant progress on increasing electricity access over the past few decades. But close to half of Nigeria's population still lack access to any kind of electricity. Even for those who do have a connection, grid access is often sporadic and unreliable. These setbacks feed a culture of heavy reliance on smoke-belching petrol and diesel generators. More than 11 million Nigerian homes, a little more than one third of the total, depend on generators, partly or wholly, for energy supply.

All this limits the chances of electric cooking, says Fay. However, the rise of off-grid electrification efforts through mini-grids offers "a very clear link" to electric cooking, he adds. Experts attribute Nigeria's progress in electricity access to increased government investment in off-grid electrification through its Rural Electrification Agency. The agency's Solar Power Naija programme, whose name includes the Nigerian word which embodies the enterprising and boisterous spirit of Nigerians, aims to connect five million homes across Nigeria to solar home systems or to a solar mini-grid by 2022.

The agency says it has made some 5,400 connections through mini-grids and connected 290,700 houses to solar home systems since 2019. These projects have helped Nigeria's installed solar capacity increase almost double from 15 megawatts (million Watts) in 2012 to 28 megawatts in 2020.

And renewable energy start-ups have come up with novel ways to make off-grid clean electricity available to homes. Lumos Nigeria and Greenlight Planet Sun King, for example, have adopted price models that allow homes to subscribe per day, week or month. Education centres such as the Renewable Energy Technology Training Institute in Lagos are training Nigerian technicians on the installation and maintenance of solar systems. In one of its recent projects, it trained 20 women on solar panel installation in Nigeria's largest slum settlement Makoko. Glory Oguegbu, founder of the institute, says these women have since trained others. In all, she says, about 750 women in the slum settlement were trained and many now have solar systems self-installed in their homes.

Despite these positive signs, off-grid connections are still not widely spread, especially in far-flung communities such as Chinenye's small, sleepy village, where she gathers wood for the evening fire.

"I have heard about cooking without firewood and I hope one day I will cook for my children without battling the smoke from my three-stone fire," she says.

--

Data research and visualisation by Kajsa Rosenblad

Animation by Adam Proctor

--

Towards Net Zero

Since signing the Paris Agreement, how are countries performing on their climate pledges? Towards Net Zero analyses nine countries on their progress, major climate challenges and their lessons for the rest of the world in cutting emissions.

--

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here .

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter or Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future , Culture , Worklife , Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

How Long Can You Keep Used Cooking Oil

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20211103-nigeria-how-clean-cooking-helps-the-climate

Posted by: brighamficepleturem.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Long Can You Keep Used Cooking Oil"

Post a Comment